In May 1985, a small group of people met in Melbourne to support each other in Zen practice.

On 25 October 2025, our Sangha gathered at CERES to celebrate forty years of the Melbourne Zen Group.

Our celebration included words from our teachers, group sharing – and cake!

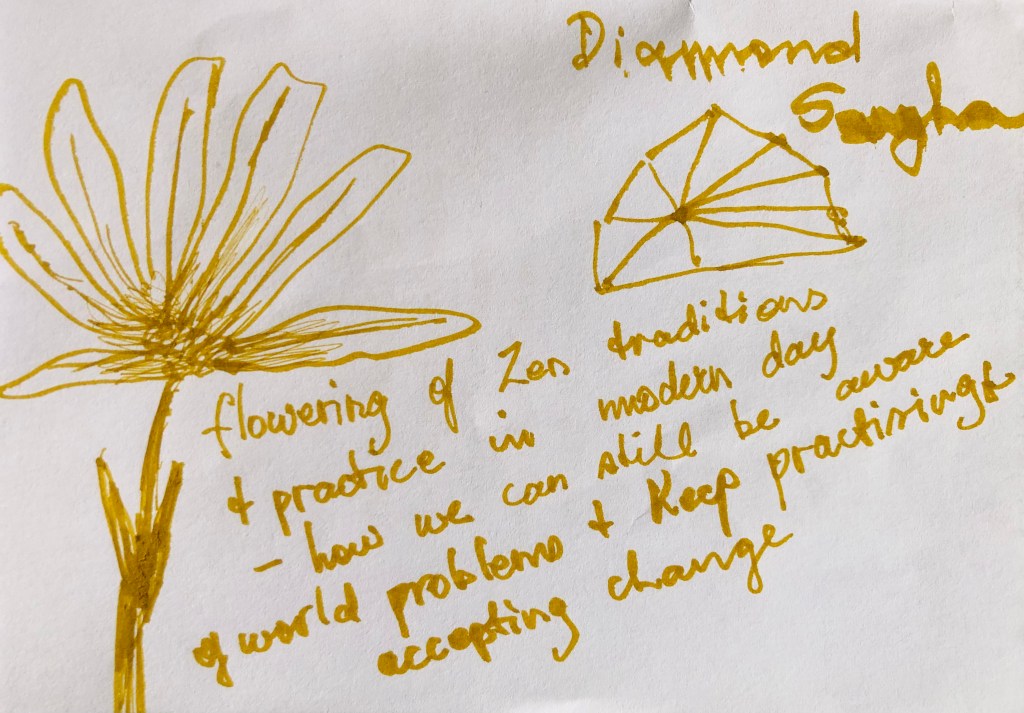

What is this Diamond Sangha? – Susan Murphy Roshi

Personal stories of the Diamond Sangha – Subhana Barzaghi Roshi

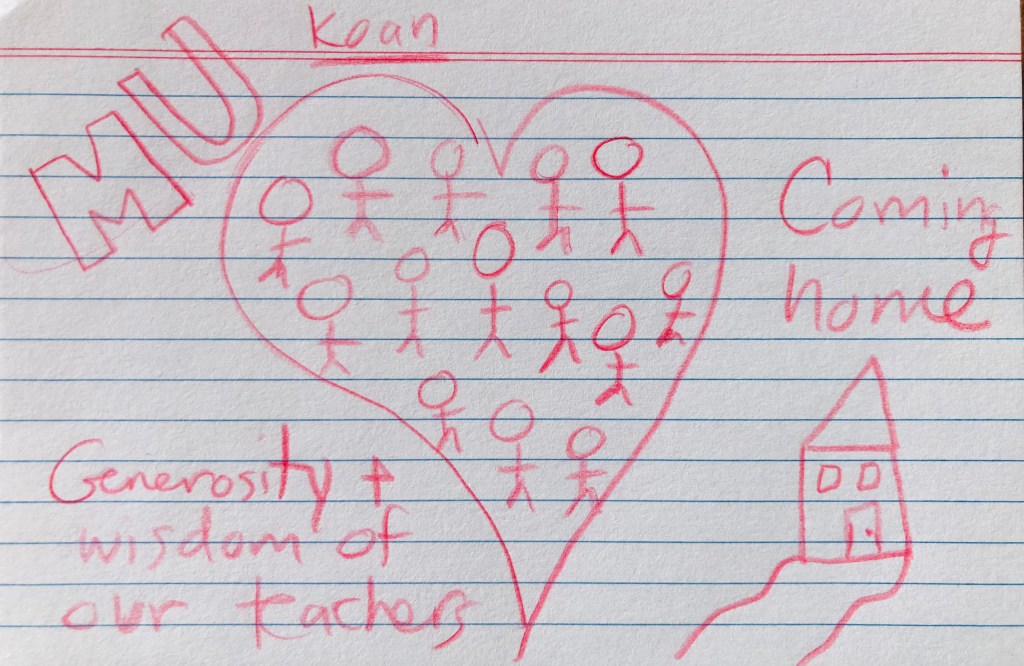

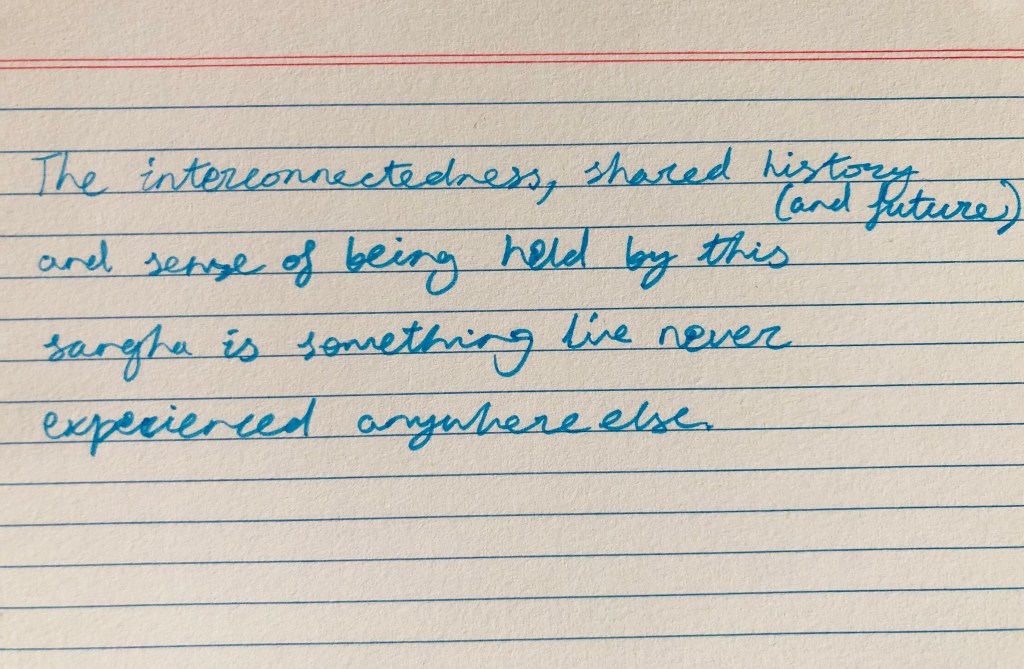

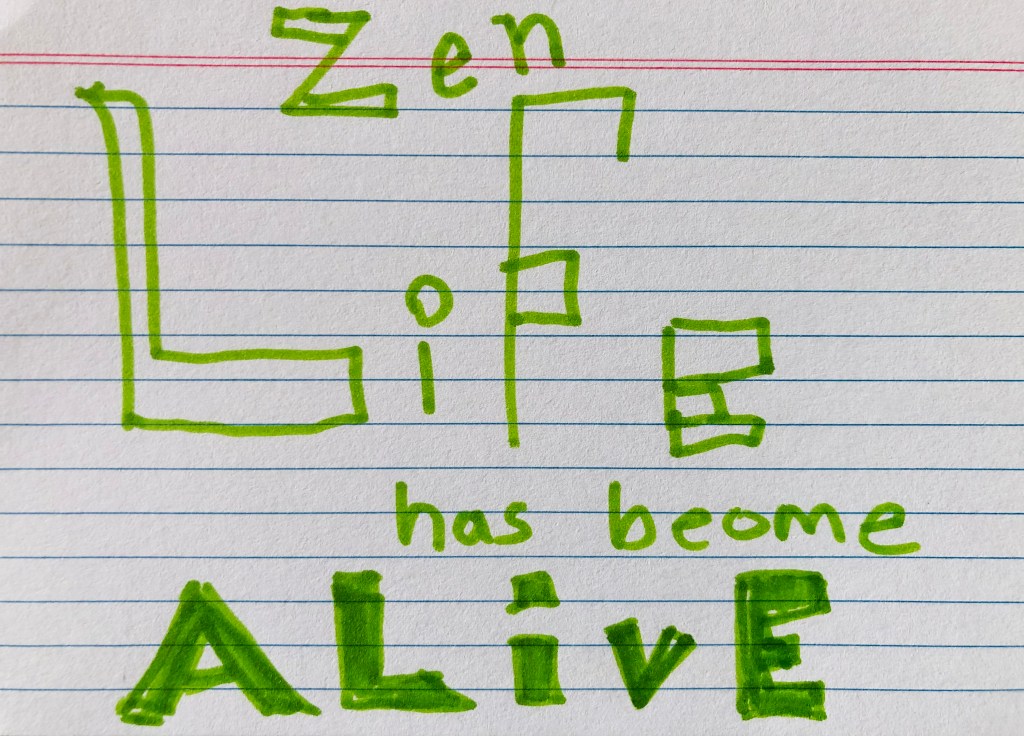

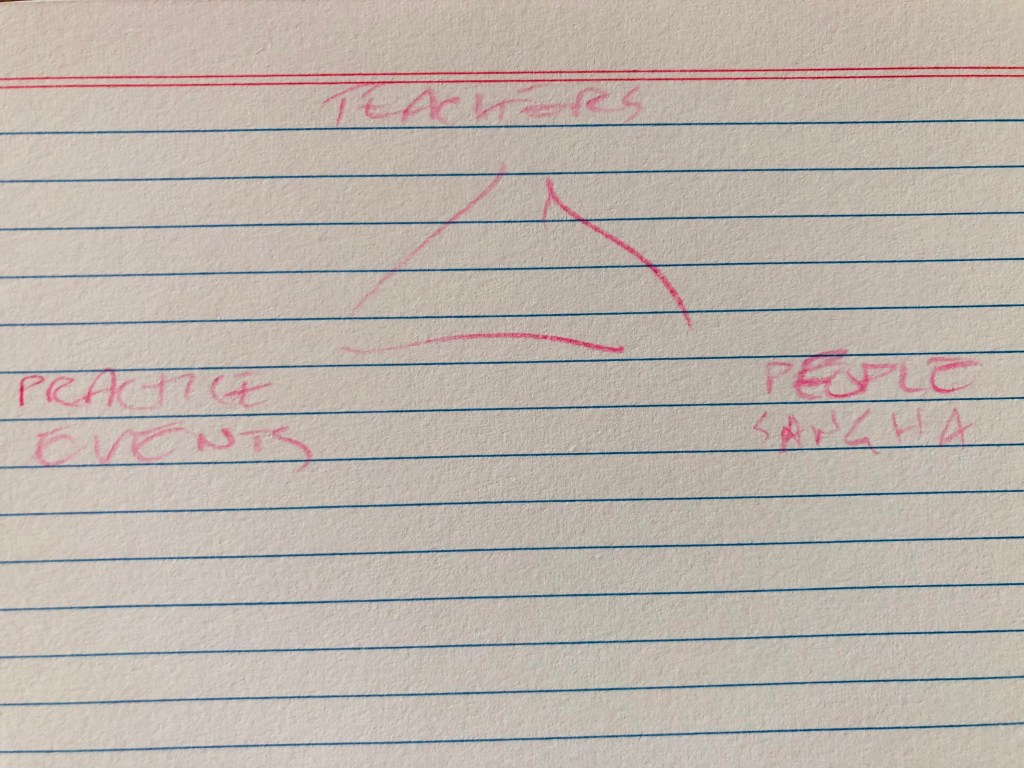

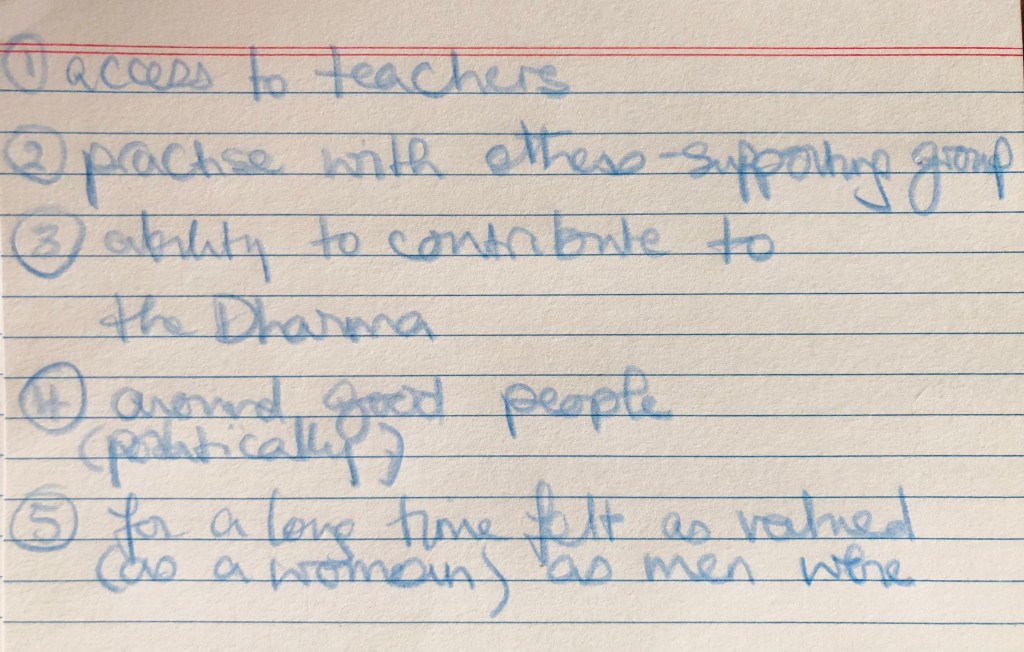

What our Sangha means to us – responses from people at the celebration

Dedication for the Melbourne Zen Group

Photos from our 40th birthday celebration

What is this Diamond Sangha in which the MZG took root?

– from Susan Murphy Roshi

In this historic moment of celebration, it seems valuable to ask just what is this Diamond Sangha in which MZG took root, 40 years ago back in 1985, and in which it has grown and found its own distinct character? What is its origin story going all the way back?

The Diamond Sangha in 2025 is a significant worldwide lay Western Zen lineage, founded by Robert Aitken in Hawaii in the 1960s and by now comprising a loose affiliation of dozens of Zen Sanghas across the USA, Australia and New Zealand, as well as Germany, Spain, Argentina, Chile and England.

One key to its coherence across time and diverse places is the rapidly growing Diamond Sangha Teachers’ Circle (DSTC), which from early days has gathered semi-regularly to enjoy personal contact and friendship, Dharma discussion and koan review. A way of keeping the Dharma clear and strong at its core. The DSTC early on dismissed the idea of exerting top-down control in any form, instead choosing collegial trust in each other and our individual dedication to the core of a rigorous shared practice. A shared Diamond Sangha Teachers’ Ethics Agreement exists, but otherwise the Diamond Sangha works deliberately as a ‘fluid fixity’ – one that took almost six decades to set down a formal description of what we hold in common.

Step into any DS dojo and you’ll find a warm welcome and a recognisable family style, roughly identical liturgy, and just minor local variations on Robert Aitken’s original expression of Zen form, which remains respected for its power of ritual containment. Above all, you should find adherence to exacting standards of genuine Zen Dharma as it was handed down to us with such care by generations of ancestors and committed teachers. And which must be handed on down with equal care from here.

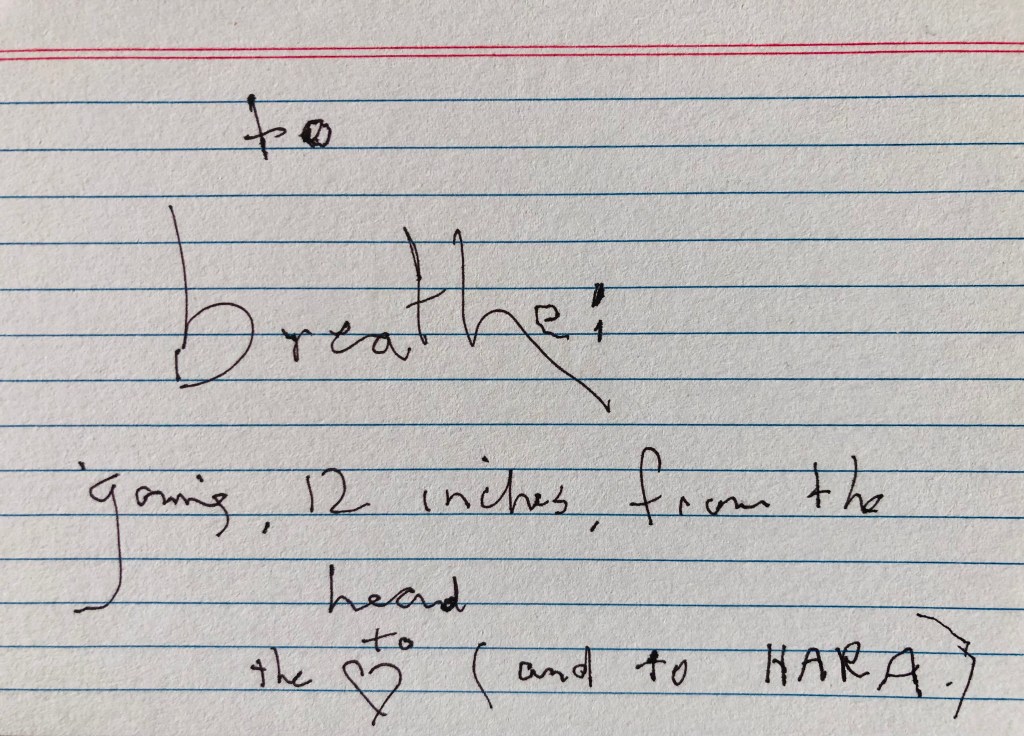

Dogen said, “When you know the place where you are, practice begins”. It is our immediate evident reality that admits us to realisation of who and what we truly are, swimming in emptiness, with practice always beginning right here. A great religious tradition carries forward a venerated past while finding itself adapting to new local conditions and ceaseless change – the only permanent thing there is.

But the place where you are – its physical being and cultural character – counts. Zen is vivid in expression, and to become mature in such expression, it must absorb change with conscious care. Robert Aitken embodied the striking task of safely carrying Japanese Zen across into a vigorous, rebellious 1960s American culture. “For the first ten years, change nothing”, he advised. First, find out what this practice, just as it is, genuinely makes possible. In time, it has become a line of Zen that venerates its origins without being pretend-Japanese.

Every such moment of cultural transition must maintain firm continuity while finding creative adaptation within sometimes dramatic changes of context. Take the original movement of Buddhism into China and the emergence of what we know as Chan (Zen) – essentially a translation of one entire world, India, into another entire world, China. Buddhism fell with relative ease into the pre-existing, deeply earthed seedbed of Chinese Daoism – to the point where ‘Dao’ and ‘Buddha’ rapidly became virtually interchangeable, changing what Chan could be in the process.

But the coming of Buddhism also necessitated a profound transliteration, as the highly abstract and disembodied formulations natural to Sanskrit in the great Buddhist sutras had to be brought across and find expression in richly compounded Chinese characters, that are decidedly earthy, bodily and concrete… a stage of acculturation that has given us much of Zen’s lively and spirited directness.

And perhaps most importantly, early in its development in mid-8thc China, Chan had to weather and find ways to respond to a period of catastrophic social upheaval following on from the An Lushan rebellion (755-763), a rupture uncomfortably like what our own time may be staring down right now. In order to be of some use in healing the vast distress of years of war, famine, the dramatic decimation of population and collapse of social order, what emerged was the brilliant means of Zen expression found by Mazu, for example, and carried on by all the great Tang Dynasty masters that followed – of directly responding in face-to-face encounters with questioners on the Way, teaching with immediacy and creativity right in the thick of what was happening.

Later these became known and collected as ‘koan encounters’, bringing us right into spontaneous, on-the-spot improvisations that directly embody emptiness wisdom alive in ‘ordinary’ evident reality, using plain words, mundane references – and requiring us to come right to the point of doing so ourselves.

As Xuedou said, Zen is ‘A natural staff, without artificial work.’ No high-flown language, just vast emptiness speaking and moving right in the vivid ‘ordinary’ – offering no explanation, just taking away all chocks holding conceptual mind in place, freeing the questioner to fall away into their own timeless self-nature. This face-to-face style of shared improvisation in the Dharma (we call it dokusan these days) is unique to Zen, a great legacy, forged and made strong by difficulty itself, that Roshi always fiercely protected from any hint of discursive weakening.

A lightning sketch of Aitken’s journey into a life of Zen practice begins with one of those mysterious origin stories. He found himself in 1944 in a wartime internment camp in Kobe after being rounded up in Guam as a civilian prisoner of war. A Japanese guard unexpectedly lent him a copy of R.H. Blyth’s 1942 book, Zen and English Literature – a detailed collection of whatever hints of a universal Zen mind Blyth could find in Western literature. Roshi was stunned by how immediately the book spoke to him. He read and re-read it ten times, said the book left him “absurdly happy despite our miserable circumstances.”

And then he discovered that Blyth himself was also prisoner in the same camp! For the next 14 months, Aitken was able to explore a wonderful, free-ranging dokusan with the book’s generous author.

Back in Hawaii, post-war, he took up study of Japanese literature and wrote a master’s thesis on Basho’s haiku that later became the beautiful A Zen Wave. For the next decade, he and Anne Aitken proceeded to seek out a variety of Japanese masters, winding up in Kamakura with their root teacher Yamada Koun, in the Sanbo Kyodan – an unusual lineage in which Yasutani, who led sesshin in Hawaii through much of the 60s before Yamada took his place, sought to reconcile the Soto and Rinzai streams of Zen back into one ground of practice.

Yamada was a masterful and deeply modest teacher who held his dojo open to Western students, including many Christian laity, some of whom became his dharma heirs. When he eventually invited Aitken to begin to teach, the Diamond Sangha was born, branching from the Japanese Sanbo Kyodan as a new and distinctively Western lay Zen expression of the lineage. It was Soen Roshi who suggested the name, honouring Diamond Head, the distinctive extinct volcano at the end of Waikiki Beach, as well as the great Diamond Sutra, so pivotal to Zen.

As Roshi has been heard to say, quoting Wumen, the whole Diamond Sangha is a “a jungle of monks at sixes and sevens”, proceeding on from there – all the way down to here.

The Diamond Sangha emerged from stiff Japanese Zen right into the heady social and political turbulence of the American 1960s. Among other things, this meant Zen absorbing the shock of feminism. Roshi encountered – and learned to admire and yield to – a resolute refusal among his women students of the patriarchal assumptions that had always dominated Zen’s male monastic tradition… a mindset that had great difficulty in even conceiving of ‘an enlightened woman’, let alone a female Zen teacher. Let alone two of them!

There was also the whole realm of Western psychologising of the self, with which Zen had to find a clear and discerning relationship. Roshi was very guarded against any blurring of the essential difference between the Dharma founded stringently in the experience of no-self, and an American culture quick to resort to a self-referenced psychologising.

And across the next seven decades, any alive form of Western Zen has also had to find ways to engage with the huge, planetary-wide issues besetting humankind: the threat of climate and environmental collapse, of militarised nuclear stand-off, of rebellion against imposed inequality and racism, and now, to virulent forms of anti-democratic despotism that would dismiss or crush human rights.

I always think of the photo of Roshi sitting in his chair each week in public during the second Iraq war, holding up a sign that explained to all passers-by, ‘The System Stinks’. The Diamond Sangha has always maintained a strong, socially responsive sense of the dharma, with a planetary reach of awareness that must go far beyond any dream of awakening as a purely personal matter or attainment. Which, finally, is a joyful fact. As Xuedou asked, “When consciousness is confined to the skull, how can joy exist?”

The Diamond Sangha began to reach Australian shores in the late 70s and early 80s, with Roshi invited to lead twice-yearly sesshin, drawn here by his amazed discovery that a small group of people in both Sydney and Perth (some of whom had sat in Japan) had begun holding seven-day teacherless sesshin! In time, his dharma successors came to lead sesshin in his place – John Tarrant, Father Pat Hawk, Augusto Alcade, and in time, Subhana Barzaghi, Ross Bolleter, myself and others.

In our Australian context, Zen met not just with blowflies, kookaburras, drought and flooding rains, but also our distinctively low-key, leaned-back Australian cultural style. And since, “When you know the place where you are, practice begins”, in time, sensitivity to Country has been finding its place in practice here, with respectful openness to the body of deep-time indigenous spiritual presence and knowledge inseparable from this place – an incomparable earth dharma of kinship and place embedded 60,000 years deep in the land. It’s our job to continue realizing Zen here in deeply respectful conversation and accord with the ancestral legacy of this continent.

We’ve seen a gradual relaxing of some of Aitken’s Japanese style of formality, with improvisations like replacing formal green tea in the early afternoon with informal afternoon tea out on the veranda, or mid-afternoon open sitting under the sky… And I want to honour our playful, rather black, upside-down sense of humour (that can rather shock our American colleagues!) and the way in which a shared loving laughter can spill over into formal ceremony, without harming any of its power.

You can feel for yourselves how all of this has flowed on into how we practice here. We now find ourselves here in Naarm, 40 years on, with a growing Sangha and new teachers emerging in the Melbourne area: with Kirk Fisher Roshi becoming MZG’s first appointed resident teacher, Kynan Sutherland Roshi steadily building a vibrant Castlemaine Zen Sangha close by, and Aladdin Jones Sensei emerging as a new apprentice teacher, also in the general Melbourne area. And more will surely follow and gradually find their place.

Subhana and I have deeply enjoyed sharing the privilege of guiding this mature and consciously independent Sangha across its last 25 years as its senior teachers, working continually to help bring Sangha and Dharma alive while steadfastly maintaining the core of our Zen practice coming down from the beginningless past – undiluted.

Personal Reflections and Stories of the Diamond Sangha

– from Subhana Barzaghi Roshi

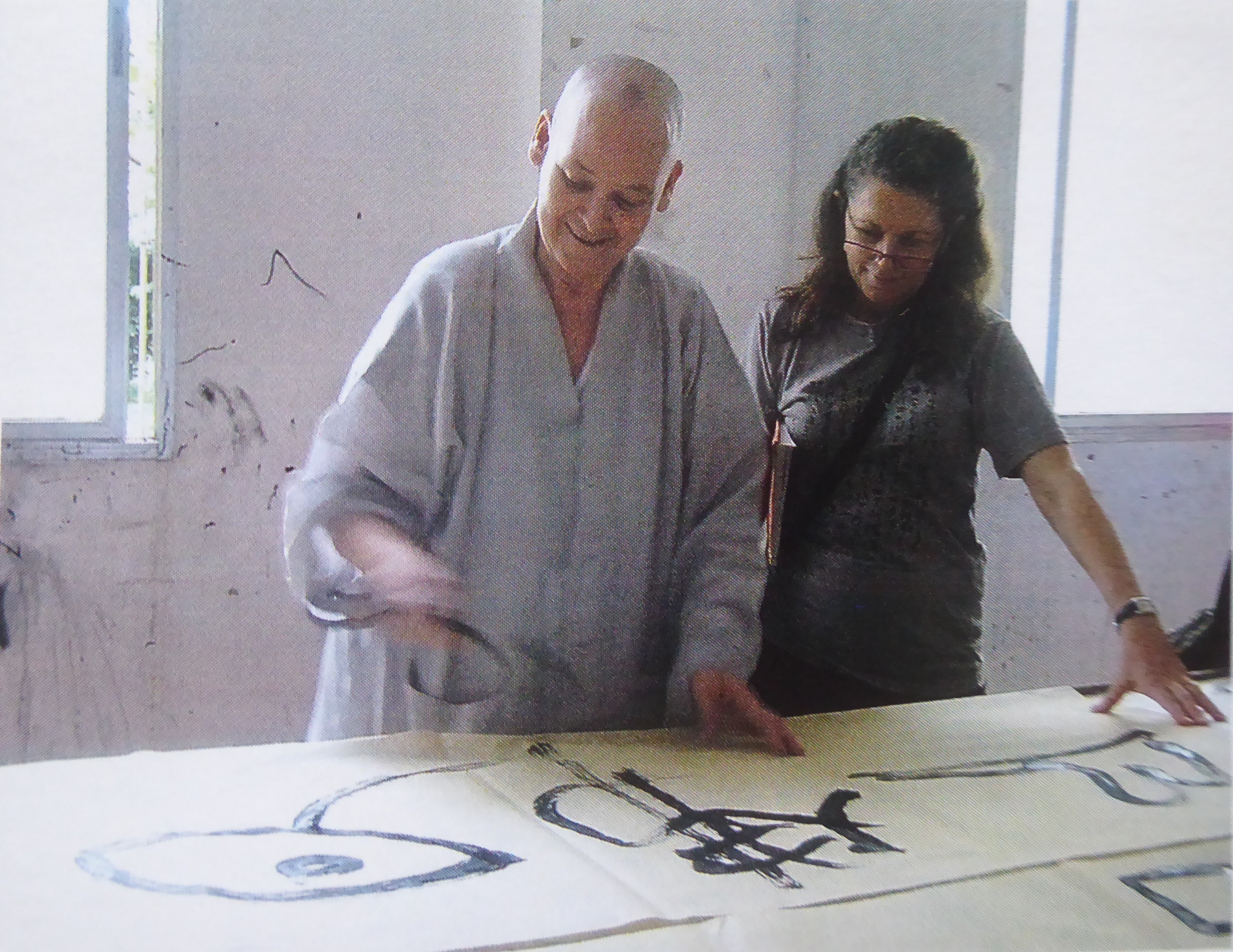

The Diamond Sangha Zen tradition was co-founded by Robert Aitken Roshi and his wife Anne Aitken in 1959, in Honolulu, Hawaii. The foundations of a Western lay Zen practice were forged from Aitken Roshi’s dedication and love of the Zen Way, his integrity and profound wisdom. He gave attention to maintaining and protecting Zen’s ancient roots, translating the pithy Chinese sages’ koans into English, adapting the ever-evolving roaring stream and carefully integrating it into our western culture. Transmitting the robust mystery of the Dharma flame, Aitken Roshi held the core teachings of the Buddha’s awakening, spreading it far and wide, igniting our dharma candle here on Australian soil in 1979.

As a long-term member and Zen teacher in the Diamond Sangha, I would like to share some personal reflections and a few stories about my experiences with Robert and Anne Aitken. These personal vignettes have influenced my ongoing engagement with Zen practice, which has spanned four decades. I hope these stories also act as an underlying motif that illustrates and reinforces a common ground, a thread of continuity that continues to shape and influence Zen practiced in the Diamond Sangha today. While there is a family style and resemblances with other Diamond Sangha Centres throughout the world, Zen comes forth out of the ground of this country, offering its own unique expression that differs from our American counterparts, Zen that is uniquely ours, that is diverse, blossoming with vitality here today.

I sat my first Zen sesshin with the ‘old boss’ Robert Aitken Roshi when I was 26 years of age in 1980 at Kerever Park, a Catholic convent and retreat centre at Burradoo south of Sydney. My connection with Roshi was immediate. He was a man of deep wisdom and integrity, and I trusted him implicitly. Dressed in black Zen robes, he had a formidable presence, especially in dokusan. It was like meeting a tiger in a tiny room that had no ground. His stern yet kind face and penetrating gaze seemed to see straight through me, to see the whole of me, something that I could not yet recognise in myself. My first sesshin was a life-changing event. The koan path plunged me into the unknown, unravelling every familiar shore of who I thought I was. The heart-mind opening experience propelled me to leave my humble abode in the sub-tropical rain forest of the Northern Rivers and travel to study with Roshi in Hawaii. Nine months after sesshin, my partner and I, with my four-year-old daughter Bija, applied and were invited to join a three-month Zen training period with Roshi at Maui Zendo in 1980.

Regular three-month in-depth immersive residential practice periods had begun in the 1970s on the Island of Maui and Koko-an Zendo in Honolulu and later at Palolo Zen Centre, which continues to offer residencies to this day. Hawaii was the powerful hub and home of the Diamond Sangha, and with Aitken Roshi at the helm, Zen flourished.

“You must walk this path for yourself. In this spirit, you invest yourself and train earnestly side by side with your sisters and brothers. It is this engagement that brings peace and realization.” – Robert Aitken

Roshi paved the way, through some stiff opposition, for us to be the first family to join an intensive live-in training period. The Diamond Sangha is a lay tradition (non-monastic); however, inviting a family with a four-year-old child’s inquisitive, delightfully buoyant nature into the Maui Zendo was a radical move. In the private back quarters of the zendo, my partner and I juggled childcare over those 3 to 4 months while participating in the daily zazen schedule that was interspersed with several sesshin. This welcome of us, as a family, left a lasting impression on me. It allowed intensive Zen training, a deep immersion in practice, without having to leave my family behind. Rather than a split dichotomy between spiritual practice and daily life, I relished the ordinary everyday life of caring for a family and the hallowed ground of zazen being woven together. I deeply valued this form of Zen training – the practice of realisation and realisation as practice generously expressing itself in the temple of daily life with the simple acts of cooking, cleaning and caring for my daughter.

There were a number of things that impressed me about Aitken Roshi. Apart from his clear-eyed wisdom and his steadfast love of the Buddha Way, he had a lifelong dedication to social and environmental activism and pacifism. He viewed social justice as integral to an engaged Zen practice that compassionately eased and addressed worldly suffering. Roshi role-modelled an engaged, non-violent activism, refusing to pay taxes during the Vietnam War and protesting down at Pearl Harbour. He embodied a spiritual life that was not separated from the socio-political and environmental spheres of life. The stream of Engaged Buddhism resonated deeply with me, as I had been involved in environmental action campaigns, protecting virgin native forests at Terania Creek in the early 80s, teaching non-violent action, protesting the damming of the wild, pristine beauty of the Franklin river in Tasmania and training with Joanna Macy. Following Roshi’s lead, Gilly Coote (SZC) and I were encouraged to set up a chapter of Buddhist Peace Fellowship in 1985. From those humble beginnings, our small group was able to invite and organise Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh’s national Australian tour in 1986.

Roshi and Anne fostered an open, inclusive style of Zen practice while equally maintaining its discipline and rigour with an uncompromising focus on living an awakened life. Foundational for Sangha relations were non-hierarchical egalitarian principles, and democratic consensus decision-making processes. All Zen Centres that are affiliated with the Diamond Sangha continue to follow these principles and practices today. I easily fell in line with these practices, having been a founding member of ‘Bodhi Farm’ – an intentional spiritual community in the Northern Rivers of NSW that was based on the same principles and decision-making process.

In the Honolulu Sangha, Roshi was faced with a group of strong, educated, independent women of the eighties and nineties with feminist leanings who refused to be iron maidens, demure tea ladies or stoic macho masters. Due to their influence, he encouraged women to step into dojo leadership roles. I spent many a sesshin sitting on the veranda of Koko-an being his Jisha. I found those strong women’s presence and voices inspiring; it opened my mind to the feminine in Zen, where women were welcome to sit equally around the ancient charcoal fire. On March 9th, 1996, at Kodoji, Temple of the Ancient Ground, I was honoured to receive Dharma transmission from Aitken Roshi and John Tarrant Roshi, making me the first female Roshi in the Diamond Sangha. Living up to the giant footsteps of my teachers, their blessings and trust in me to hold up the light of the Dharma, has been humbling and deeply moving. Aitken Roshi’s empowerment of women in Zen was another first and somewhat radical even for Zen in the West. Within the broader landscape of Zen, there is a significant and growing number of female teachers in the Diamond Sangha – we currently have nine female Zen Roshi in Australia.

Anne Aitken

Anne co-founded the Diamond Sangha with her husband Robert Aitken. She bought both properties, Koko-an Zendo in Honolulu and Maui Zendo on the Island of Maui. She was a respected elder in the Dharma, completing the full koan curriculum twice. She could have been a teacher in her own right but declined to teach formally. I liked to think of her as the grandmother of the Diamond Sangha.

I first met Anne Aitken at my first three-month training period in 1980. Anne heard I could sew, so she asked me to make muumuus for her (no, it’s not a new koan, although it could have been). A muumuu is a Hawaiian smock; a long dress often made from lovely, large-flowered, colourful Hawaiian printed fabric. Unbeknownst to me back then, I was stitching a connection that would eventually span three decades.

Anne had an infectious smile and a heart as wide as the world that warmed and welcomed everyone she met. Anne was Anne. She inspired others through her love of the practice and her fearless embrace of life and death. She was loved, and she loved generously. In her motherly fashion, as she had done with so many other Zen women, she had taken me under her wing.

When I began attending the Zen teachers’ meetings in Hawaii in the mid 90s, I was sitting in an all-male circle of strong-willed, independent Zen teachers. Luckily, Anne came and rescued me from the boy’s club each afternoon. While the blokes were arguing the finer points of Zen philosophy, the gals were out eating ice-creams, laughing and enjoying a dose of the feminine.

One of the most poignant memories I have of Anne that still touches me today was when I was visiting Hawaii. It was a balmy evening in Honolulu, and a restaurant offered a more relaxed atmosphere than the formal mealtime etiquette of Koko-an Zendo. It was indeed a special treat to be dining out with my old teacher Robert Aitken Roshi, and with Anne and a few of Roshi’s dharma heirs.

Anne and I sat at one end of the table giggling, playing games like two mischievous schoolgirls, lost in our own intimate world of girl talk, while the men were down at the other end of the table. Anne had aged beautifully; soft grey waves of hair framed her pale face and clear blue eyes. I delighted in her colourful Hawaiian dresses, those long muumuus that flowed and caressed the bare floorboards. That evening, Anne wore a similar dress to the one I had been assigned to carefully patch and hand hem, summers ago during a Zen training period on Maui.

I had only recently been invited to be an apprentice Zen teacher in the Diamond Sangha, which was a rather daunting honour. I was a young, green novice teacher at thirty-nine, and stepping into the teaching role was both terrifying and, for brief moments, an exhilarating, heart-felt intimate experience. Most of the time, I confess, I secretly felt an overwhelming sense of inadequacy to uphold this noble task. The mantle of responsibility weighed heavily on my shoulders. Below the shoulders, I was plagued with doubts and uncertainty. Why me? What did they possibly see in me, I wondered. Perhaps, I was not up to the task nor the responsibility they had entrusted to me. I was just a hippie child of the 70s, from the beat generation, who lived in a spiritual community in a rainforest, who had an epiphany in India on hearing the Buddha Dharma and had been besotted by the teachings of liberation and freedom ever since. But alas! This freedom-loving young woman was no longer knee-deep in pleasure; she was now anxious and burdened.

I admitted to Anne how inadequate I felt in my first forays into teaching, how I was quite anxious before giving a public Dharma talk. Among other things, Anne had been an actress before she had met Roshi. Performance anxiety was a familiar old friend to her; she had wrestled with that daemon. She confided in me that before she stepped on stage, she would take herself in hand and encourage herself, “I can do it, I can do it”. She felt the fear, but just stepped through it and onto that edgy stage. She said that once she opened her mouth, the anxiety transformed into excitement and energy for the role. She then turned to me, took my sweaty hand in her parched, strong, graceful fingers and looked me straight in the eye, and calmly said, “You can do it, you can do this, dear”. Tears welled up inside me; my anxiety melted with her love and support. The vulnerable, anxious part of me felt seen and heard. I recalled the poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s words, “Perhaps everything that frightens us is something helpless that needs our love”.

There we were, like two peas in a pod, two Dharma soul sisters, one green young shoot, one wise old elder, holding hands, completely oblivious to the other guests and the restaurant chatter. Tears ran down my face, unashamedly. Here in this curious place, in the back seat of a restaurant, was heart-to-heart transmission outside the scriptures; this was a blessing from the feminine.

Even years later, whenever the drum sounded, and I walked out across the field into the Zen Temple to give the daily Dharma talk, I often imagined Anne holding my hand, walking next to me, her voice singing in my heart, her words ringing through my bones, “You can do it”. Those words forged each step towards the Dharma hall; my heart then settled back into the great matter where there is nothing to fear.

Anne’s outstretched palm connected me to a long line of sincere, awake female practitioners down through the generations, who courageously spoke the truth, often in times and in cultures where a woman’s role was very prescribed and relegated to the hearth. For those female ancestors, it took courage to transform their fears, to rise above the patriarchal voices of suppression and the familial expectations of filial piety. Voices that insisted they be the dutiful daughter, mother or wife, pressuring them into silence and back into a conservative mould. It takes boldness to resist inadequacies that keep one small and scared, and instead find a voice that is authentic, speaking the truth of what you know in the hem and bones of a life. Anne’s gift, transmitted from hand-to-hand, lives on in the expansive heart that calls one to a freedom that is greater than our fear. It’s a message for all practitioners of the Way: “You can do this”.

After Anne’s death, her old black robes were cut up and her muumuus were handed on to the women who knew and loved her. Pieces of Anne’s muumuus were sewn into this beautiful blue woman’s Rakusu that I am wearing today. It was made for me by the women in the California Diamond Sangha. It travelled south to this great land and was given to me as a Transmission gift. These pieces of cloth rub up against my breast and remind me that the fabric of our lives is intimately connected and stitched together. Anne’s radiant smile, her strength of mind and fearless embrace of life and death carry me forward in moments of uncertainty to a greater mysterious tapestry of who we truly are. I am deeply grateful to Anne for her muumuus, ice-cream and holding my hand.

The formation of the Diamond Sangha nourished the seeds of Zen’s early beginnings in the West. The careful transmission of the lamp over several decades has borne fruit. Zen has matured, ripened and integrated into this country. There was a special experience that I had that highlights the integration of Zen into our Australian landscape. It is well known that male lyrebirds sing, mimicking elaborate sounds of other birds, performing complex songs to impress and attract females. They have also been known to mimic the sound of a camera shutter, car alarm and chainsaw. One morning in sesshin, I was awoken in the early hours before dawn by a cacophony of birdsong, along with the sounds of bells and clappers, and the tock, tock of the Hanh. I sat up, checked my watch – it was only 4am – and wondered why the Jikki was ringing the wake-up bell so early. No lights were on in the dojo. What was going on? It was then that I realised this was the lyrebird mimicking the sounds of sesshin. It had heard and learnt a new repertoire, echoing and singing back to us, Wake up! This moved me to tears. I felt Zen had really landed wholly and fully into this landscape, and the beautiful lyrebird was affirming the Way.

Melbourne Zen Group

I was first invited to teach in MZG in 1993, when I was a newly minted young apprentice teacher. John Tarrant consulted Father Pat Hawk Roshi, who had been a foundational teacher for the MZG and had been coming here to do sesshin for about six years. Many students felt a deep fondness and loyalty to Pat, but he was no longer able to travel due to health issues. I found Pat generous and supportive in offering a hand over, so I took tentative steps in teaching sesshin. In the first 5 years of teaching, I was doing back-to-back sesshins with SZC and MZG, which proved to be exhausting and too much, so I suggested the MZG invite Susan Murphy to co-teach here. Twenty-five years since then, we have supported and shaped the practice here within a strongly egalitarian, independent and consensus decision-making based Sangha. It is wonderful to see new teachers beginning to naturally appear within Victoria, not just in the MZG with Kirk Fisher as its first local teacher, but with Kynan in Castlemaine and now Aladdin also beginning to step into teaching in the Melbourne region.

A deep bow to the Practice Facilitators

In the first 30 years, MZG did not have a resident teacher, only visiting Zen teachers. As a way to support the Sangha, I recommended that the MZG Committee invite and train a group of committed members to be practice facilitators. This model had been very effective in SZC in supporting dojo leadership roles for regular zazen nights, caring for the rituals and forms of zazen and providing orientation for new people. The strength of the MZG is primarily due to all those people over many years who have taken up the responsibility and stepped into the practice facilitator role; many of you are here today. A deep bow of gratitude to all the practice facilitators for your service in caring for this Sangha.

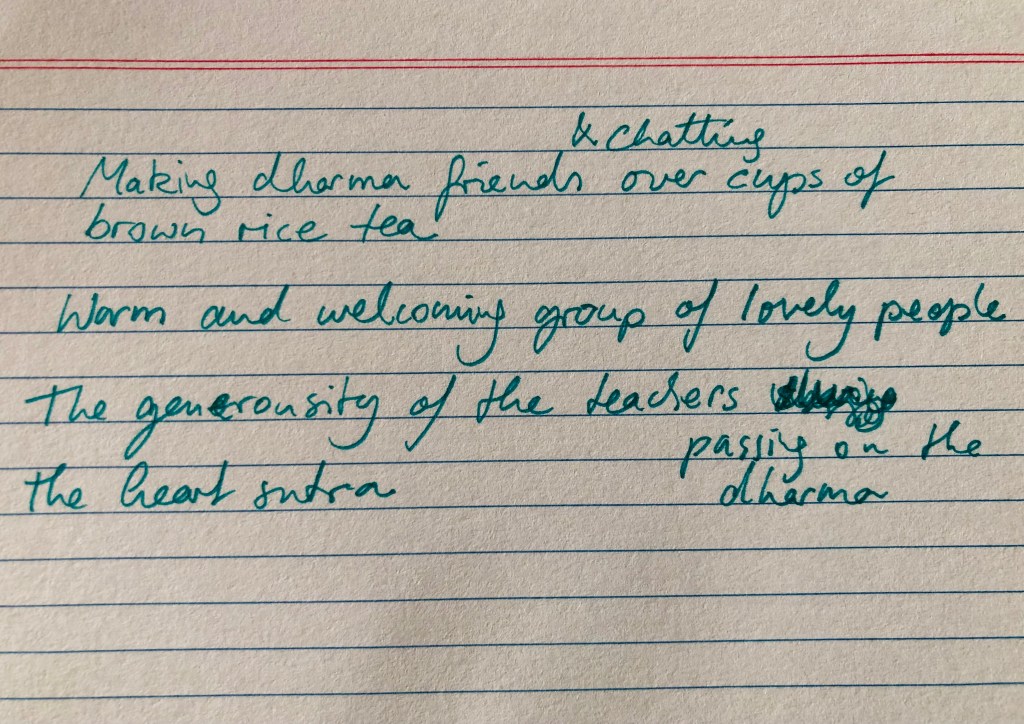

The Buddha declared to Ananda that spiritual friendship was not half of the spiritual life but the whole of the spiritual life. We sit to make ourselves and each other whole again. That wholeness is celebrated here in this circle today. I feel like a bit of a den Dharma mother and feel proud of what the MZG has achieved through the struggles, trials and joys of practicing together and supporting one another. MZG is a thriving, diverse, caring Sangha. You have created a safe refuge, a welcoming, open, inclusive Sangha, a culture of awakening for the benefit of all beings.

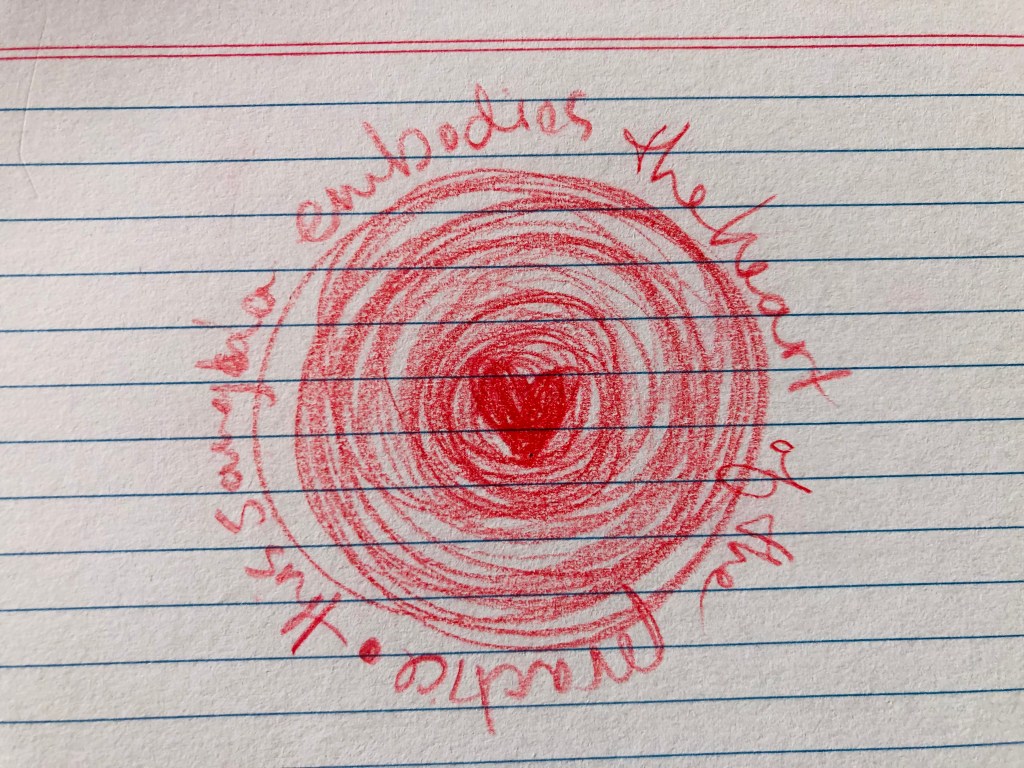

Dedication for the Melbourne Zen Group

Susan Murphy Roshi wrote this dedication for our Sangha for the occasion of the CERES dojo opening. We used the dedication on our 30th birthday event and for our 40th birthday event.

Dedication

In streets and homes, gardens and workplaces,

On trams and crowded trains, bike-paths and busy roads,

Deep inside each timeless moment of our crowded, tender lives,

The light of Dharma comes awake, in Manna Gums and human eyes,

Tawny frogmouths, cats on fences, dogs in their barking,

Toddlers with their tears, old ones with complaining hips,

And each of us exactly, just as we are.

May the moonlight of wisdom freely shine, un-obscured

And not held back, in all we do and touch and say.

This is our path, our practice and our gift,

To each other and all beings, passed down through the years,

Now carefully carried forward, warm hand to warm hand:

Through ceaseless change, one light endures.

May we retain this mind and extend it forth, to mend our fractured world,

Maturing in Buddha’s wisdom, reaching out to help the many beings,

And protecting our great Earth, that nourishes this Mind.

All beings throughout space and time

All bodhisattvas, mahasattvas,

The great Prajna Paramita.

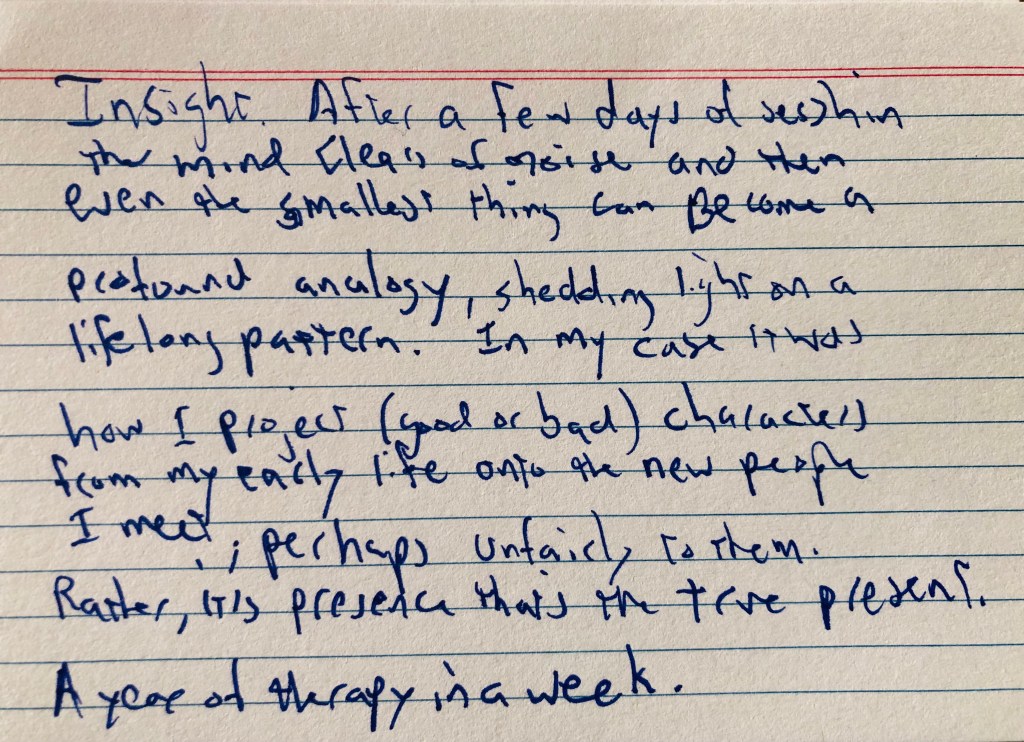

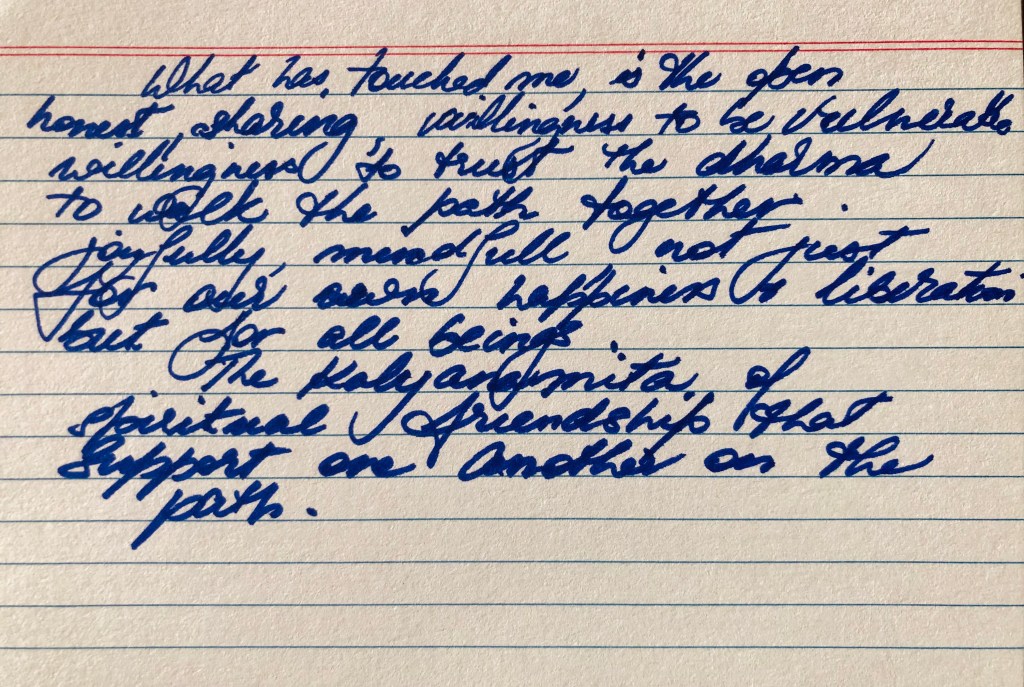

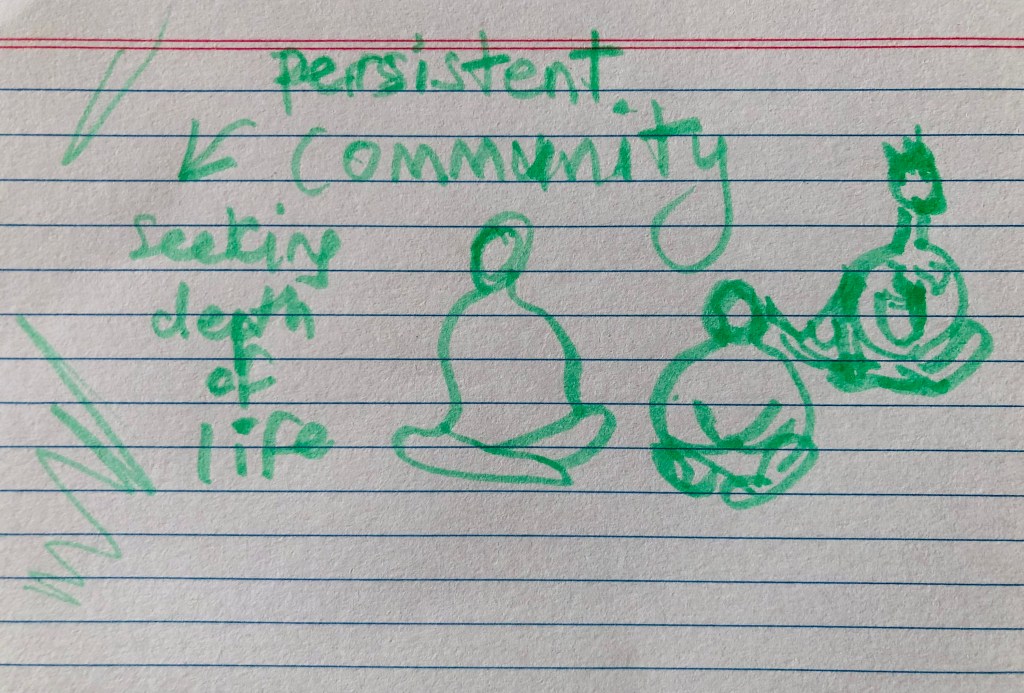

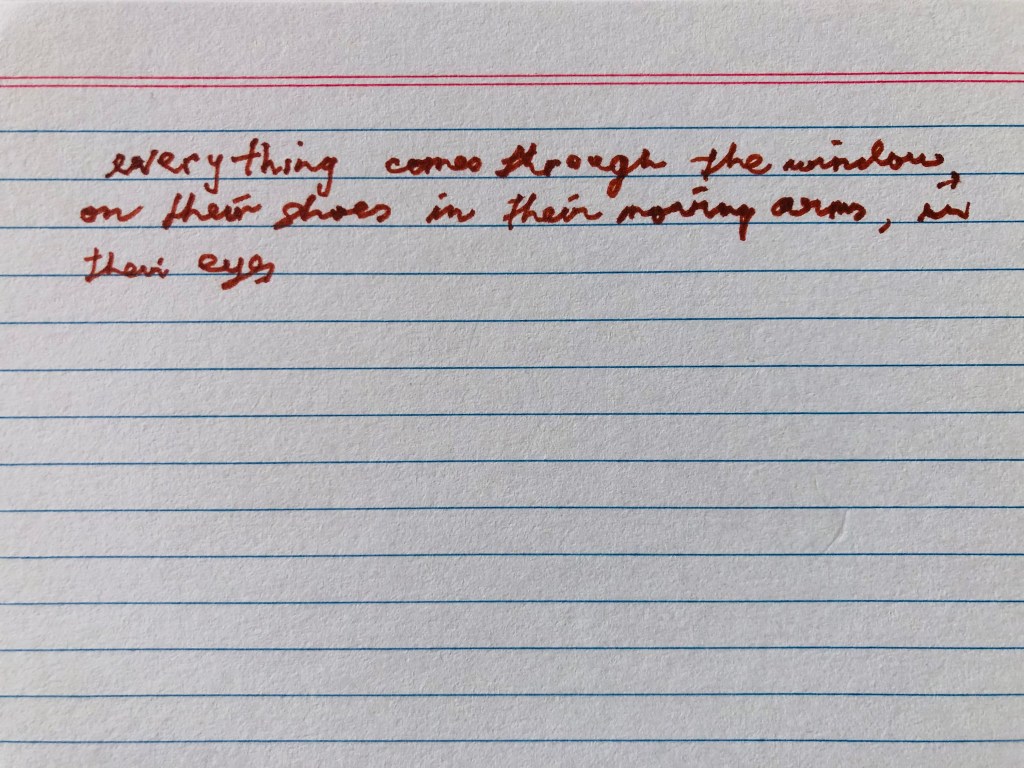

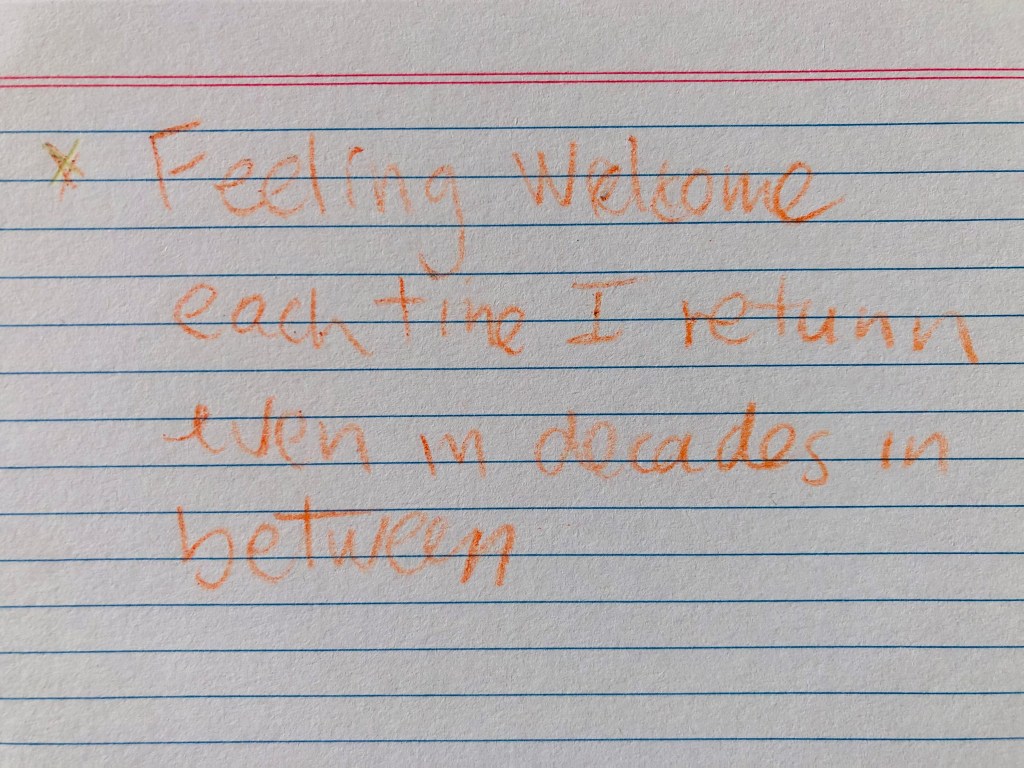

What does our Sangha mean to us?

Responses from Sangha members who were at the 40th celebration –

A chronology of our Sangha

Thanks to Paul G for trawling through old MZG newsletters and pulling out the dates –

Pre-1985: Informal group meditation in Melbourne

1985-1989: First formal meeting of a small group of people who had been to sesshin with Robert Aitken – and who later formed the MZG (including Mal Backus, Phil Pegler, possibly Jill Jameson, probably Michael Backerra). The group meets at the Buddhist Society of Victoria in Richmond and at KEBI (now known as Kagyu Evam Institute – a few doors north of its current location).

1990-1995: Pat Hawk visits Melbourne to teach at sesshin (including at Greyfriars in 1991). Other visiting teachers at this time include Geoff Dawson, Augusto Alcalde and apprentice teachers Subhana Barzaghi and Ross Bolleter. MZG incorporated in 1993. Phil Peglar invites the MZG to sit at the newly built Dragon Sky Zendo at his house, and initiates weekly Saturday sits and monthly Full Moon Zazenkai.

1995: Pat Hawk no longer able to travel to travel from USA to teach sesshin in Melbourne.

1996-1998: In 1996, Subhana Barzaghi receives transmission to teach from Robert Aitken Roshi and John Tarrant, and in 1998, the MZG invites her to be the group’s main visiting teacher.

1999: On Subhana’s recommendation, the group invites apprentice teacher Susan Murphy to teach in Melbourne. Susan teaches at an end-of-month zazenkai at Daiji An (newly built by Jill Jameson at her Hoddles Creek home). The group starts sitting at the Clifton Hill Zendo on Saturdays and for Full Moon. A notice is placed in the group’s Vast and Ordinary newsletter, appealing to some “benevolent person” to offer the group cheap rental for a single MZG dojo. At Subhana’s suggestion, the group create the role of Practice Facilitator, with Meg Irwin and Neti Shanahan being the first PFs.

2002: Group invites Susan to join Subhana as an MZG group teacher. Susan begins offering phone dokusan to MZG students. First sesshin at Adekate Camp, at Dean, near Ballarat.

2003-2006: An anonymous donor offers the MZG $35,000 to establish a dojo fund. Dojo subcommittee forms, begins fundraising to increase the dojo fund and explores different options for the group to get its own dojo. First sesshin at Mt Nagle, Queenscliff. First sesshin at Casa Pallotti. Subhana and Susan gift the group with a white ceramic Buddha. Practice Facilitator Pool established. MZG 20th birthday celebrated at Clifton Hill Zendo in May 2005 – about 12 people meet for lunch and cake.

2007: Closure of Clifton Hill Dojo announced. First mention of CERES as a possible dojo site.

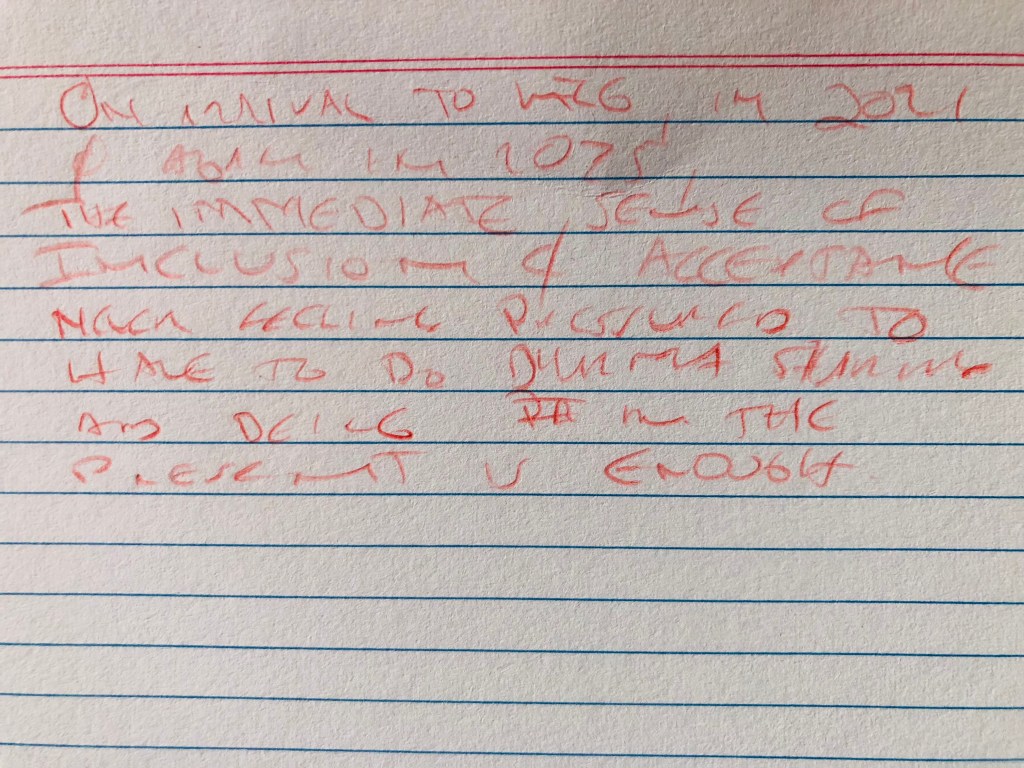

2009–2010: Move to CERES Learning Centre, with dojo opening in 2010. New bronze Guanyin figure purchased for altar at CERES.

2010: Death of Robert Aitken

2012: Death of Pat Hawk

2015: MZG 30th Anniversary – 34 people meet at CERES for group sharing, then go to Sandy and Jill B’s place for dinner.

2016: Work begins on the Learning Centre Meditation Garden. Kirk Fisher made apprentice teacher.

2019: Diamond Sangha 60th Anniversary

2020-2021: Covid. Group introduces online sitting, online sesshin, an online Sangha soiree and an online Sangha games night.

2023: Kirk’s Transmission Ceremony.

2024: Formalisation of Kirk’s teaching relationship with the MZG.

Historic photos of our Sangha

You must be logged in to post a comment.